Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Original of 14 January 2018, updated to 18 June 2020, 16-18 November 2020

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2018-20

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/CRD17.html

Centrelink is an Australian government agency within a super-portfolio department now styled 'Services Australia'. It is the conduit through which welfare payments under scores of programs reach beneficiaries. During the second half of 2016, Centrelink added yet another data matching program to its portfolio, and established what it called a Online Compliance Intervention (OCI) scheme.

OCI acquired from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) the annual income figures for each Centrelink welfare recipient, divided them by 26, and then looked for discrepancies between that averaged fortnightly figure and the fortnightly declarations made to Centrelink. Also as part of the scheme, the longstanding procedures for checking anomalies were closed down, the onus of proof was switched from the agency to the welfare recipients, debts were declared to exist if the recipients failed to prove their innocence, and the debts were promptly passed to debt collectors for aggressive action. Astonishingly, no-one in the agency, ATO or anywhere else detected the hare-brained assumption embedded in the scheme.

Hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients were relentlessly pursued for repayments, and many had substantial amounts deducted from their ongoing benefits. Advocates yelled from the roof-tops. There was widespread and prolonged media coverage, pillorying the scheme as 'Robo-Debt'. The 'Privacy Commissioner' was every bit as useless as she and her two predecessors have ever been. The Ombudsman and a Senate Committee accepted the overwhelming evidence from advocacy agencies, and published reports that showed the scheme up for what it was. Yet the government chose to brazen it out and ignored them.

The majority of this document describes the first 18 months of the process, from mid-2016 to the end of 2017. The following brief postscript was added in mid-2020, to mark the scheme's demise, and the repayments ands 'reparations' phases.

The OCI / Robo-Debt scheme ran onwards through 2018 and almost to the end of 2019. In mid-2019, it was reported that the agency claimed that, during the 3 years from mid-2016, the scheme had raised over half-a-million debts and recovered over $300m (Barbaschow 2019). The costs that the agency admitted to included "AU$72 million in 2015-16, AU$110 million in 2016-17, and AU$193 million in 2017-18" (Barbaschow 2019). Together with $231m in 2018-19, and probably even larger costs in 2019-20 (Barbaschow 2019), the scheme's admitted establishment and operational costs probably exceeded $750m.

For over 2 years, the agency successfully avoided any of the affected people getting their cases before the court. Eventually, Victorian Legal Aid managed to get a case in front of the Federal Court. The agency ignored its (purely nominal) obligation to be a 'model litigant', and waited until the court door to accept that it would lose the case.

In mid-November 2019, the government announced withdrawal of the scheme (Barbaschow 2019). On 27 November, the government caved in and agreed to a consent judgment against it on all counts (Karp 2019, Easton 2019).

In May 2020, the government announced the value of the repayments it was going to commence making from 1 July 2020. "The total value of refunds, including fees and charges, is estimated to be at AU$721 million [relating to] 470,000 [erroneously created] debts" (Barbaschow 2020). This figure compares with $640m claimed at one stage as the total that had been collected. It appears that about 1.2 million debts may have been raised during the course of the scheme, but this does not mean that the remaining c.700,000 debts were justified. Many would have been unresolvable, and there were no doubt strenuous efforts to keep the count down.

The repayment process was also going to be challenging, because some people who the government owed money were no longer in the Centrelink system. Moreover, the matter did not finish there. The government declared that 'for legal reasons' it would not apologise. That was tacit recognition that the courts would be awarding substantial damages to many litigants in any case, and an apology might cause the amounts involved to balloon even higher (Henriques-Gomes 2020).

The Commonwealth continued its extremely poor behaviour in the matter as the class action commenced in June 2020. The judge had to order the government to amend its defence to match its public announcements. The lawyers for the litigants, meanwhile, called for interest to be paid on amounts paid, and raised the possibilities of arguing for exemplary damages, and bringing a misfeasance in public office claim against Ministers, for "acting in bad faith" (i.e. despite knowing that what they were doing was wrong) (Estcourt 2020).

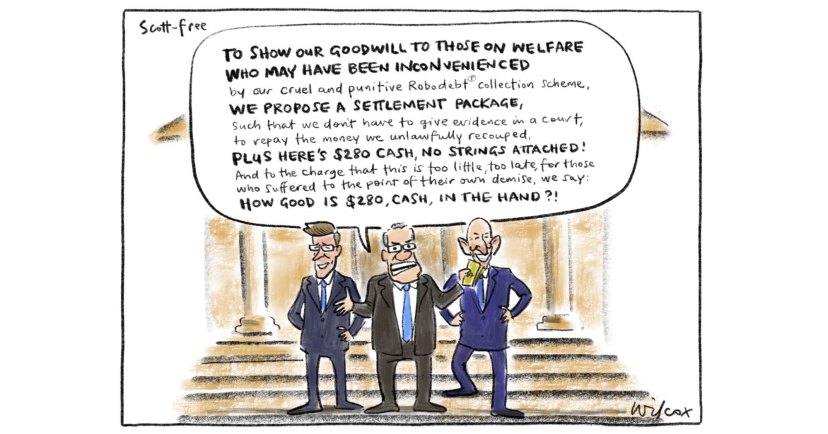

The Commonwealth maintained its bad behaviour all the way to the court door (Doran 2020). It escaped with a settlement of a further $112m, of which a significant chunk will go to the litigation lawyers and the financiers. The number of aggrieved parties is of the order 400,000, and hence the reparations averaged $280 per person. As ever, no mention was made of the millions paid by the Commonwealth to its solicitors and barristers, nor of the millions of public servants' time wasted on the case instead of on activities of benefit to the Australian public. The Commonwealth also agreed to cancel a further $398 million in debts wrongly raised. So the acknowledged value of unjustified debts raised was between $1.1 and $1.2m. Cartoonist Wilcox summarised the arrangement:

It appears that not one public servant, and not one politician, suffered in the least for their breaches of the law, or for their utterly unprincipled, incompetent and plainly idiotic behaviour. The Minister, both prior to the scheme commencing and during its last year, was the blunder-prone Stuart Robert. The Westminster notion of Ministerial responsibility has long been inoperative in Australia, and Robert's announcement smugly conveyed that none of it was his fault. Meanwhile, the chief executive of the agency at the time of the blunder, Kathryn Campbell, was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia for "distinguished service to public administration". Anecdotal evidence suggests that the most guilty of the parties, i.e. the Deputy Secretary/ies, First Assistant Secretaries and Assistant Secretaries who drove the debacle, all escaped the agency to greener pastures, probably to wreak further havoc on the public from some other comfortable seat, and in due course accept their Public Service Medals.

Robo-Debt was:

Centrelink is the Australian government agency responsible for distributing welfare payments. Currently, it transfers about AUD 160 billion p.a. from the public purse to millions of people, under about 100 programs across many categories of recipient, including age and disability pensions, unemployment benefits, and family, child care, disabled care and study support. In most cases, the amount of the benefit depends on the person's other sources of income during the relevant period, and generally the relevant period is the fortnightly benefits payment cycle. About one-third of the adult population of 18 million receive some kind of benefit, and about half of all households. There is of course enormous scope for fraud, error and waste. Considerable effort is invested in discovering where overpayments have occurred, and seeking restitution. Official estimates of the scale of overpayments are in the range $1.5 - 4.0 billion p.a., i.e. 1.0 - 2.5% of the gross payments.

In the second half of 2016, Centrelink launched a new system that was intended to improve the efficiency of the agency's processes for discovering overpayments and pursuing the resulting debts. The new arrangements were referred to internally as the Online Compliance Intervention (OCI) system.

The implementation of OCI resulted in a large proportion, and very large numbers, of unjustified and harmful actions by the agency. This gave rise to serious public concern, and attracted a great deal of media attention. Because the system involved a novel, automated decision-making feature, the media referred to it the 'robo-debt' scheme. Two external investigations were conducted into the operation of the OCI. The agency was forced to make large numbers of changes to the scheme in order to overcome the deficiencies and reduce the harmful impacts on the agency's clients.

This brief case study provides an overview of the events from mid-2016 to mid-2017. It draws on the two investigative reports, over 20 substantive media articles, and a small number of other sources. The investigating agencies were not successful in extracting from Centrelink a reliable and consistent set of data on the early operation of the project. As a result, statistical analysis is beset with difficulties, and hence some of the evaluative comments have had to be expressed in cautious terms.

For many years, the income that welfare recipients have declared to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) in their annual tax returns has been compared against the fortnightly income declarations that recipients are required to make to Centrelink. The large numbers of material discrepancies that were found were prioritised, and the highest-priority cases pursued. Centrelink sought further information from the recipient, and, where necessary, then acquired more detailed data from the recipient's employer(s).

A new Online Compliance Intervention (OCI) system was implemented in the second half of 2016, with full roll-out from September 2016. The agency's intentions were to process more cases, recover more overpayments, reduce the labour-intensiveness of the process, lower some of Centrelink's costs and transfer other costs from the agency to the individuals concerned. The key changes made included automation of the comparisons between the Centrelink and ATO data, automation of notices to targeted recipient, and shifting of the burden of data acquisition and capture to recipients. The details of the matching and selection process (the "risk matrix") remain obscure. This may be partly justifiable, on the grounds that broadcasting details of social control methods invites countermeasures; but it is also open to interpretation as bureaucratic furtiveness.

ATO income data is collected as a total figure for the financial year, whereas Centrelink benefits are calculated fortnightly, based on the income figures reported to it by each recipient. The design of the new system embodied the assumption that income reported to the tax agency was earned at a consistent rate over the relevant period of employment.

A key cost-saving element of the design was the abandonment of the cross-checking of details against employers' records which had previously been undertaken. Under the new scheme, where an apparently material discrepancy was discovered between the ATO and Centrelink data, a letter was now automatically generated and sent to the recipient. Recipients were required to demonstrate their innocence of the accusation, by providing evidence that showed that they had not been overpaid. The recipient was required to challenge the accusation, and to produce supporting documentation satisfactory to Centrelink. A further change made when the OCI system was implemented was that Centrelink ceased its policy of accepting copies of bank statements where payslips issued by the employer were unavailable. Only after sustained pressure did it accept that copies of bank statements could still be acceptable.

If the recipient failed to challenge the accusation, or failed to deliver evidence that Centrelink would accept, the agency automatically declared that a debt existed, in many cases added a 10% 'recovery fee', and put debt collection measures in place. Where the person was on ongoing recipient, this involved deductions from recipients' ongoing payments. Otherwise, the matter was passed over to private-sector debt-collectors.

It appears that at no stage did Centrelink perform any systematic assessment of the extent to which, and the circumstances in which, the assumptions underlying the new scheme were unjustified and would result in unreasonable decisions and actions. At no stage did Centrelink or its portfolio agency, the Department of Human Services, discuss with ATO the nature of the ATO's data or the design of the OCI system. Further, no consultations were undertaken with representatives of Centrelink's operational staff who deal directly with benefit recipients, nor with advocacy organisations that represent recipients' interests.

Public furore erupted during January 2017. This was despite the information coming to public notice during the close-down period between Christmas and New Year, and the summer holiday period which runs through to late January. The media dubbed the fracas 'robo-debt', and pursued it with vigour. Centrelink intensified public anger by sustaining a state of denial throughout, and suppressing information about the program. The following analysis summarises what became apparent from active journalism, analysis by the better-educated and more persistent among the benefit-recipient population, public interest advocacy and the official investigations.

The largest single factor in the debacle appears to have been the use of an algorithm that was clearly inappropriate to the circumstances of a significant proportion of the relevant population. Many benefits recipients earn income from short-term, casual and/or seasonal employment, and hence they work variable numbers of hours per fortnight. In the new system, however, the ATO earnings information was apportioned evenly over the relevant period of employment in order to establish an estimate of the income earned in each fortnight of that period. Centrelink then based its decisions on overpayments and debts on that estimate. For the many people whose income is unevenly distributed, the assumption is seriously problematical, and results in debts being raised that are significantly higher than justified, and in a moderate proportion of cases simply wrong.

The second major concern was the automated nature of the decision-making. For what appears to be the first time, people's lives were placed at the direct mercy of a machine, without human consideration of the matter prior to action being taken that was harmful to the people concerned.

A further factor was the huge increase in the number of cases that were being pursued as a result of the new arrangements. Centrelink had projected that the number of overpayment reviews processed each year would leap almost forty-fold from 20,000 to 783,000. Yet the agency appears not to have realised that this would give rise to very large increases in the numbers of transactions conducted not only in the online system, but also at the call-centre and front counters. It might have been expected that additional staff would have been put in place, particularly for the inevitably fraught transitional phase. In fact, it appears that the agency had been forced to comply with Government-imposed reductions in head-counts, such that call-centre and front-counter staffing was actually lower than it had been prior to the new system being launched.

A fourth problem was the difficulty that confronted recipients in understanding the accusation. The letter was vague, and demanded a level of intellectual capacity and online expertise that many benefit recipients do not have.

The next issue was people's inability to achieve contact with Centrelink in order to gain clarification of what the letter meant, and what documentation was acceptable. The early rounds of letters did not even contain the relevant phone-number. Many recipients were unable to get through to the overloaded call-centres, with many reporting delays of 3-6 hours before a call was answered. People in rural areas had to travel long distances to Centrelink offices. In regional and suburban offices alike, people had to wait in long queues to get access to under-resourced and under-informed counter-services. Further factors compounding the problem were the short 21-day period provided within which the documentation had to be provided - which in some cases straddled the always-slow summer holiday period - the difficulty in applying for an extension, and the rigidity with which the automated system applied the time-limit.

That was followed by the challenge of finding documentation (if the person had received it) or acquiring it (if they had not). Many circumstances exist in which recipients simply cannot get access to such documents. The problem was compounded by the agency's refusal to accept copies of bank statements as evidence of the payments that the person had received.

A seventh issue arose once documentation had been submitted. It proved difficult to get the attention of anyone in Centrelink in order to get corrective action taken and to achieve confirmation that the problem had been fixed. In principle, most of this activity was supposed to be performed by the individuals themselves, using the online facility. In practice, some benefits recipients do not have Internet access, many were unable to cope with the interface, and significant numbers of cases are sufficiently complex that they fall outside the scope of the online system and have to be processed manually.

An eighth issue was the precipitate passing of matters to private-sector debt collectors. This was done where the alleged debtor was no longer a benefits recipient, and it appears that almost half of all debts raised under the OCI scheme fell into this category. The agency's behaviour in relation to its use of its own powers, and the use of debt collectors, appears not to be subject to an effective regulatory framework.

One benefit recipient published an opinion piece in a national newspaper that was highly critical of the scheme. The Minister added fuel to the fire by releasing personal data about the recipient in an endeavour to publicly discredit her. This abuse of institutional power, and probable breach of data protection law, was argued by advocates to have further chilled the behaviour of recipients who might otherwise have communicated details of the agency's blunders to the public.

Even as late as May 2017, the agency had still undertaken no consultations with any of the stakeholders. Advocacy organisations that sought to convey the concerns to the agency were not provided with any opportunityto do so, and were left with no other option than to pursue the matter through the media.

The Ombudsman conducted an investigation into the limited parts of the problem that fell within the Office's scope. The Report identified many serious administrative and procedural failings. The Privacy Commissioner, on the other hand, declined to conduct a review.

It did, however, become apparent that Centrelink had devised the scheme in such a manner that it side-stepped many of the privacy-protective measures that had previously applied to its data matching activities. This was achieved by a mechanism that had the appearance of deviousness. Where a particular identifier, the Tax File Number (TFN), is used in a matching procedure, the process is subject to a longstanding and enforceable statutory Code. Under the new arrangements, Centrelink does not send the TFN to the ATO, but instead sends each individual's name, date of birth and historical addresses. The ATO then looks up the person's TFN and uses that to extract the data that it holds about the individual. This strategem slides the new scheme out from the statutory Code. It is instead subject only to a weaker and unenforceable set of guidelines, which the agency is free to apply, adapt or ignore, as it sees fit. The agency prepared a 'program protocol', but suppressed it - although a copy emerged in the public domain almost a year later.

A Senate Committee investigated the matter, and found large numbers of problems across the length and breadth of Centrelink's practices, some of them specific to the OCI program but many of them extending well beyond it. The Committee majority made a long series of recommendations for change. The Government Senators, who constituted a minority of the Committee, acted primarily as representatives of their Party, and for the most part sought to undermine the Committee's investigation.

Doubtless, some cases of welfare fraud were discovered, as has always been the case with such processes. In addition, some instances of over-payment of benefits due to reporting and timing errors are likely to have been found. The proportion and number of successes and of failures are difficult to estimate, however, because, despite the scheme being subjected to two investigations, Centrelink provided only limited and inconsistent data about its operation.

Interpolating among the partial and inconsistent data that emerged in a variety of contexts, it appears that 200,000-220,000 benefits recipients were sent letters. For various reasons, some thousands of people did not receive their letters, with the result in most cases being that a debt was automatically raised without the person being even aware that the process was happening. It seems that about 20% of people who received letters were able to convince Centrelink that the accusations the letters contained were wrong. It further appears that debts were raised in relation to about 60% of the benefits recipients to whom letters were sent. Many of the debts were in the thousands of dollars. At least 15,000 debts were cancelled, and at least 25,000 were reduced, many of them apparently to small amounts. However, that data was provided by Centrelink in early 2017, while a very large backlog of complaints was as yet unprocessed.

Table 1 attempts a summary scorecard for the first period of operation of the new system. The final line of the table overstates the scheme's success, in that it includes some proportion of subsequently cancelled or reduced debts, and some proportion of debts that stand, but which would not have stood had the recipients been able to understand the accusations and present evidence to disprove them.

| Category | Indicative No. | Indicative % |

| Letters sent | 210,000 | 100 |

| Evidence accepted | 42,000 | 20 |

| Available to action | 168,000 | 80 |

| No further action taken | 42,000 | 20 |

| Debts raised | 126,000 | 60 |

| Debts later cancelled (min.) | 15,000 | 7 |

| Debts later reduced (min.) | 25,000 | 12 |

| Debts pursued in full | 86,000 | 41 |

It appears that, at the very best, only about 40% of the letters sent to benefits recipients were fully justified, and a maximum of a further 12% were partly justified. There were substantial negative impacts on more than half the people who were sent letters. All were subjected to considerable pressure and required to scurry around trying to understand the accusations, find documentation, cope with a complex online system, and wait in queues at call-centres and counters. Some were subjected to reductions in benefits that were unjustified. Many welfare recipients live hand-to-mouth with no cash reserve, and some also have high-interest debt to service. In such circumstances, reductions in benefits directly result in additional financial hardship. Some ex-recipients were subjected to aggressive debt collection procedures, again without justification. No recompense was provided to those individuals who were wrongly accused, wrongly billed, wrongly had amounts deducted, or were wrongly pursued for imaginary debts.

By mid-2017, pressure through the media, and from the Ombudsman and the Senate Committee, had forced Centrelink to introduce a manual review step prior to the letter being sent, i.e. to abandon the automated decision-making element, to significantly modify many aspects of the procedures, to much improve their communications with benefits recipients, and to establish more effective services for people who tried to make contact with the organisation. In the meantime, staff morale had plummeted, and a number of damning insider assessments had been published. The agency's credibility with the public, never high, was now in tatters.

It took until mid-2020 for the government to cave in, and until late 2020 for the government to be forced to admit to a further huge tranche of unjustified debts raised, and to provide minuscule reparations of c. $200 per person.

Major public policy programs are inevitably complex, and are inevitably burdened with legacy features, technologies and organisational cultures. Government agencies that are responsible for such programs are under continual pressure to combat fraud, avoid waste, improve operational efficiencies, and reduce staff-counts and costs. They need imagination to address the challenges, and they need scope to investigate alternative approaches.

However, agency executives have a responsibility to proceed cautiously, and to identify and manage the risks involved in changed procedures. The risk assessment processes used must not be limited merely to agency-internal and political perspectives. They must encompass the impacts on external users, and on all categories of individuals and organisations potentially affected by the changes. It is difficult to see how effective impact assessment could be performed without conducting active consultation with frontline staff and advocacy organisations, and applying participative design principles in order to reflect the information so gleaned in the scheme's design.

Centrelink's 'robo-debt' fiasco abjectly failed all reasonable expectations of professionalism on the part of the agency and its executives. It is extraordinary that those responsible for it could justify their continued employment after such disastrously bad project conception, performance and implementation. There is, however, no record of anyone being sacked, or even disciplined. The government executives involved appear to perceive the principle of accountability to apply to other people, not to themselves. Regulatory agencies are hamstrung by inadequate scope, powers and resources. The quality of public administration can be expected to plummet still further, until and unless standards are imposed on the public sector, and effective regulatory arrangements are put in place.

Ombudsman (2017) 'Centrelink's automated debt raising and recovery system' Commonwealth Ombdusman, April 2017

Senate Committee Report (2017) 'Design, scope, cost-benefit analysis, contracts awarded and implementation associated with the Better Management of the Social Welfare System initiative' Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs, 21 June 2017, including:

DMP (1994) 'Guidelines for the Conduct of the Data-Matching Program' Delegated Legislated under the Data Matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990, October 1994, nominally enforceable, but applicable only if the matching process uses the Tax File Number (TFN)

OAIC (2014) '[Advisory] Guidelines on Data Matching in Australian Government Administration' Privacy Commissioner, June 2014, unenforceable

Centrelink (2016) 'Data Matching Protocol', undated, but apparently of mid-2016, suppressed by Centrelink for a year, and only disclosed incidentally by another agency as an attachment to a letter of 16 May 2017 by the Privacy Commissioner responding to a Senator's questions

OAIC (2017) Vacuous statements by the Privacy Commissioner, January-March 2017

DHS (2017) 'If you owe us money, you'll need to pay us back' Department of Human Services, 2016-17

Whiteford P. & Crosby M. (2015) 'FactCheck: Is half to two-thirds of the Australian population receiving a government benefit?' The Conversation, 11 May 2015

McLean A. (2016) 'H_u_m_a_n_ _S_e_r_v_i_c_e_s_ _t_o_ _r_e_c_o_u_p_ _A_U_$_4_b_ _w_i_t_h_ _a_u_t_o_m_a_t_e_d_ _w_e_l_f_a_r_e_ _o_v_e_r_p_a_y_m_e_n_t_ _s_y_s_t_e_m' zdNet, 5 D_e_c_e_m_b_e_r__ _2_0_1_6

Knaus C. (2016) 'Centrelink debt notices based on 'idiotic' faith in big data, IT expert says' The Guardian, 30 December 2016

Knaus C. (2017) 'Centrelink's debt mistake: 'There's no way I could explain to them'' The Guardian, 3 January 2017

Hall B. (2017) 'What should you do if you get a Centrelink debt letter?' The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 January 2017

Butler J. (2017) 'Centrelink Phone Lines Jammed, People Forced To Call Hundreds Of Times Just To Get Through' Huffington Post, 4 January 2017

McLean A. (2017) 'Centrelink investigation not opened by privacy commissioner' zdNet, 6 January 2017

Yoo T. (2017) 'Turnbull's former digital tsar says 'blind faith' in data led to the Centrelink debt debacle' Business Insider, 6 January 2017

Cowan P. (2017) 'Ombudsman to investigate Centrelink data matching' it News, 9 January 2017

Belot H. & McGhee A. (2017) 'Centrelink debt recovery program to undergo changes following public criticism' ABC News, 16 January 2017

APF (2017) 'The Imminent Threat of Automated Government' Media Release, Australian Privacy Foundation, 18 January 2018

Fox A. (2017) 'As a struggling single mother, Centrelink terrorised me over ex-partner's debt' Fairfax Media, 6 February 2017

Coyne A. (2017) 'Govt refuses to budge on Centrelink data matching' itNews, 7 February 2017

Coyne A. (2017) 'Inquiry to be held into Centrelink data matching system' itNews, 8 February 2017

Malone P. (2017) 'Centrelink is an easy target for complaints but there are two sides to every story' Fairfax Media, 26 February 2017

Knaus C. & Farrell P. (2017) 'Centrelink recipient's data released by department to counter public criticism' The Guardian, 27 February 2017

Knaus C. (2017) 'Welfare recipients to blame for Centrelink debt system failures, Senate inquiry told' The Guardian, 8 March 2017

Butler J. (2017) 'Centrelink 'An Unworkable Mess', Employee Tells Robodebt Inquiry' Huffington Post, 28 March 2017

Towell N. (2017) 'Centrelink hits 21,000 families with bogus FTB debts' Fairfax, 30 March 2017

Knaus C. (2017) ''Reasonably clear' Alan Tudge's office broke law in Centrelink case, says Labor legal advice' The Guardian, 3 April 2017

McLean A. (2017) 'Privacy Foundation calls for human intervention in Centrelink debt collection' zdNet, 3 April 2017

Towell N. (2017) 'Not reasonable or fair' Ombudsman slams Centrelink's robo-debt scheme' Fairfax, 10 April 2017

Knaus C. (2017) 'Centrelink's debt data-matching failed government's privacy guidelines, campaigners say' The Guardian, 19 April 2017

Coyne A. (2017) 'Centrelink targeting $980m from data matching expansion' itNews, 19 May 2017

Coyne A. (2017) 'Centrelink ... Finally releases robo-debt program protocol' it News, 19 May 2017

Duckett C. (2017) 'Centrelink urged once again to halt robo-debt program' zdNet, 18 May 2017

Coyne A. (2017) 'DHS hired Data61 three times to help fix its robo-debt program' itNews, 15 August 2017

O'Mallon F. (2017) 'How many Centrelink debts were wiped in your Canberra postcode?' The Canberra Times, 17 December 2017

Doctorow C. (2018) 'Australia put an algorithm in charge of its benefits fraud detection and plunged the nation into chaos' BoingBoing, 1 Feb 2018

_______________

Barbaschow A. (2019) 'Human Services has now wiped over 31,000 'robo-debts'' zdNet, 21 May 2019, at https://www.zdnet.com/article/human-services-has-now-wiped-over-31000-robo-debts/

Barbaschow A. (2019) 'Human Services has spent AU$375m on 'robo-debt'' zdNet, 13 February 2019 , at https://www.zdnet.com/article/human-services-has-spent-au375m-on-robo-debt/

Barbaschow A. (2019) 'Government backflip as robo-debt income automation paused' zdNet, 19 November 2019, at https://www.zdnet.com/article/government-backflip-as-robo-debt-income-automation-paused/

Barbaschow A. (2020) 'AU$721 million in robo-debts to be returned as Australian government admits error' zdNet, 29 May 2020, at https://www.zdnet.com/article/au721-million-in-robo-debts-to-be-returned-as-australian-government-admits-error/

Amato v Commonwealth FCA VID611/2019, Federal Court of Australia, 27 November 2019, at https://www.comcourts.gov.au/file/Federal/P/VID611/2019/3859485/event/30114114/document/1513665

Karp P. (2019) 'Government admits robodebt was unlawful as it settles legal challenge' The Guardian, 27 Nov 2019, at https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/nov/27/government-admits-robodebt-was-unlawful-as-it-settles-legal-challenge

Easton S. (2019) 'Robodebt defeated: Commonwealth caves in and accepts debt and 10% penalty both invalid' The Mandarin, 27 November 2019, at https://www.themandarin.com.au/121517-robodebt-defeated-commonwealth-caves-in-and-accepts-debt-and-10-penalty-invalid/

Henriques-Gomes L. (2020) 'All Centrelink debts raised using income averaging unlawful, Christian Porter concedes' The Guardian, 31 May 2020, at https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/may/31/all-centrelink-debts-raised-using-income-averaging-unlawful-christian-porter-concedes

Estcourt D. (2020) 'Senior ministers may be hauled into court over robo-debt class action' The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 2020, at https://www.smh.com.au/national/senior-ministers-may-be-hauled-into-court-over-robodebt-class-action-20200616-p55338.html

Doran M. (2020) ' Federal Government ends Robodebt class action with settlement worth $1.2 billion' ABC News, 16 November 2020, at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-16/government-response-robodebt-class-action/12886784

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor in Cyberspace Law & Policy at the University of N.S.W., and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 4 January 2018 - Last Amended: 18 November 2020 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/DV/CRD17.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy