Roger Clarke's Web-Site

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024

Infrastructure

& Privacy

Matilda

Roger Clarke's Web-Site© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2024 |

|

|||||

| HOME | eBusiness |

Information Infrastructure |

Dataveillance & Privacy |

Identity Matters | Other Topics | |

| What's New |

Waltzing Matilda | Advanced Site-Search | ||||

Review Version of 20 October 2022

Roger Clarke and Katina Michael **

© Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 2022

Available under an AEShareNet ![]() licence or a Creative

Commons

licence or a Creative

Commons  licence.

licence.

This document is at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/MSRA-ACIS.html

When organisations sponsor interventions into economic and social systems, it is normal for them to conduct an evaluation of the risks that the intervention entails. Conventional, standardised approaches to Risk Assessment are heavily committed to the perspective of the sponsoring organisation. The interests of other stakeholders may be considered, at least to the extent that they are perceived as representing constraints on the achievability of the sponsor's objectives. This narrows the focus to only those stakeholders that are perceived to have sufficient power, and overlooks legitimate stakeholders.

Many interventions have substantial impacts, variously by design, and in the form of side-effects and collateral damage. Most interventions embody application of information technologies, and the technologies that are being deployed now extend beyond data processing, into automated inferencing from data, automated decision-making, and automated action. Further concerns arise from the increasing opaqueness inherent in many technologies, whereby inferencing is fuzzy, decision-making is empirically-based and hence a-rational, actions are unexplainable and unauditable, redress is unachievable, and accountability is destroyed.

This article seeks a practicable mechanism whereby the interests of relevant players can be reflected in the assessment of interventions. Given that Risk Assessment (RA) is mainstream within organisations, the article investigates how RA can be augmented, with the intention of leveraging that familiarity and easing the absorption of external perspectives into each organisation's internal evaluations. The proposed Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA) technique is described, exemplars of processes with some of the technique's characteristics are identified, and an illustrative case study is used to demonstrate its potential efficacy.

In performing their functions, organisations initiate new interventions into existing social and economic processes. Interventions can be of many kinds, including new or amended legislation, regulatory measures of some other kind, adaptation of institutional or sectoral infrastructure due to shifts in market power, changes in business processes, and new forms and new applications of transformative or disruptive technologies. With most interventions, one organisation is recognisable as the primary driver, in this article referred to as the 'sponsoring organisation'. In the context of interventions in which information technology (IT) plays a significant role, the term 'system sponsor' is adopted for the organisation that develops, implements or adapts a system or process, causes it to be developed or implemented, or for whose benefit the initiative is undertaken (Clarke 2015b).

During the seven decades since computing began to be applied to data processing, applications of IT have migrated far beyond the conversion of data into information. They now draw inferences from clusters of information, support decision-makers, and even make decisions based on information and inferences, support individuals taking actions driven by those decisions, and even directly implement decisions. Systems have burst out beyond organisational boundaries, linking pairs, chains and networks of organisations, and extending out to individuals. From the outset, it has been apparent that IT-based systems are capable of substantial impacts and implications, ranging from the highly beneficial to the very harmful, sometimes foreseen and managed, but in many cases unintended, unanticipated, or foreseen but ignored (Authors). The growth in scale and scope of IT-based systems has been accompanied by greater potential value to at least some participants, but also by considerable increases in the likelihood and seriousness of harm.

To cope with the expanding scale and scope of IT-based projects, more rapid development techniques have been deployed. These feature even less quality assurance than was applied to the simpler systems of the past. The result has been an ongoing, poor record of plannability, delivery to time and budget, and performance reliability, maintainability and adaptability. Academics have spent a great deal of time studying the reasons underlying project shortfalls, especially project failure; but failures persist, and the quality of service of many ongoing systems remains low (Dwivedi et al. 2015).

Because of the high costs involved, the high risk of inadequate performance and failure, and the collateral damage arising from misconceived, poorly designed and poorly implemented interventions, the impacts and implications of interventions are recognised as requiring evaluation, preferably at several checkpoints along the way. A wide variety of evaluation techniques exists. Mainstream techniques applied by business enterprises include business case development and analysis, and risk assessment. Techniques with broader scope include cost/benefit analysis and technology assessment.

Most evaluation techniques have a very tight focus on the interests of a single stakeholder, whereas other approaches are more amenable to consideration of the concerns of multiple players. The analysis reported in this paper is concerned with the interests of all affected parties. The paper's purpose is:

to seek a practicable mechanism whereby the interests of relevant players can be reflected in the assessment of interventions

The paper commences by summarising key insights from stakeholder theory. This enables consideration of the extent to which each of the wide variety of evaluation techniques can reflect the interests of multiple parties. An alternative with promise is argued to be an adapted form of the conventional and well-documented business process of Risk Assessment (RA), referred to here as Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA). As a preliminary test of the proposition, prospective drivers for adoption of the technique are identified. A summary is then provided of an illustrative case study of a large-scale government intervention popularly referred to as 'Robodebt'. The case is used as a basis for showing how MSRA could have been applied in order to avoid the serious harm that the project gave rise to.

The term 'stakeholders' was coined as a counterpoint to 'shareholders', in order to bring into focus the interests of parties other than the corporation's owners (Freeman & Reed 1983, Laplume et al. 2008). In IT contexts, users of information systems have long been recognised as stakeholders, commencing with employees in the 1970s, in the context of intra-organisational systems. With the emergence of inter-organisational systems (Barrett & Konsynski 1982), and then extra-organisational systems (Clarke 1992), IT services extended beyond organisations' boundaries, and hence many suppliers and customers, both corporate and individual, became users as well.

The notion of stakeholders is broader than just users, however. It comprises not only participants in information systems but also "any other individuals, groups or organizations whose actions can influence or be influenced by the development and use of the system whether directly or indirectly" (Pouloudi & Whitley 1997, p.3). The term 'usees' is usefully descriptive of such once-removed stakeholders (Berleur & Drumm 1991 p.388, Clarke 1992, Fischer-Huebner & Lindskog 2001, Wahlstrom & Quirchmayr 2008, Baumer 2015).

The stakeholder notion has been subjected to further analysis and discussion during the almost four decades since it emerged. One analysis distinguishes stakeholders based on power, legitimacy and urgency (Mitchell et al. 1997). An approach based on ethics might dictate that 'legitimacy' has primacy. On the other hand, a strong tendency has been evident, in industry and government practice alike, for attention to be paid only to the interests of those stakeholders that are capable of significantly affecting the success of the project -- as perceived by the project sponsor (Bryson 2004). The interests of the sponsoring organisation or system sponsor are treated as paramount, the interests of powerful participants and usees are relegated to the role of constraints on the achievement of the primary organisation's objectives, and the interests of other participants and usees that lack power are commonly marginalised or ignored. Ackermann & Eden (2011), for example, recommend that an organisation sponsoring an intervention concentrate primarily on 'players' who have high power and high interest, while keeping an eye open for 'context-setters' (with high power but low interest) and 'subjects' (with low power but high interest), whose potential to oppose may need to be neutralised, but who might be able to be enlisted as allies (p.183). In that highly-cited article, the notion of stakeholder legitimacy is sublimated as 'interest', and the authors acknowledge that "strategic management of stakeholders [is] problematic ... because it seems a manipulative -- and thus somehow `illegitimate' -- activity" (p.180). See also Achterkamp & Vos (2008).

Many evaluation techniques exist, with widely varying approaches and foci. This analysis excludes consideration of activities that are merely concerned with checking an organisation's compliance with 'soft' regulatory instruments (such as codes of ethics and industry standards), or with a particular statute, delegated legislation such as a formal Code, or a broad body of law (such as safety, data privacy or consumer rights).

Mainstream techniques within organisations include soft or justificatory forms of Business Case Development (BCD) (Schmidt 2005), and more exacting techniques such as Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (DCF) (SoW 2013), Net Present Value Analysis (NPV) (Dikov 2020), financial sensitivity analysis and financial risk assessment. All of these depend on quantification, and in particular on the expression of costs and benefits in financial terms. The analysis is generally undertaken from the perspective of a single legal entity or government agency. In the case of interventions in which IT plays a major role, that single entity or agency is typically the system sponsor (Clarke, Davison et al. 2020).

Some single-organisation assessment techniques extend to factors that cannot be readily reduced to financial values, whose representations are referred to as 'non-quantifiable' or 'qualitative' data. These approaches include internal Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) (Stobierski 2019) and Risk Assessment. The second of these is central to the work presented in this paper. All of these techniques are highly organisation-centric, and only reflect interests of some other party if that stakeholder is perceived by the organisation to be sufficiently powerful to be able to affect the organisation's capacity to achieve its objectives.

Evaluation techniques exist with a broader frame of reference. Technology Assessment (TA) is concerned with the evaluation of potential impacts and implications of a particular technical capability (OTA 1977, Garcia 1991). Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) (Morgan 2012) evaluates the effects on the physical environment (commonly summarised as air, land and water) of a development project such as a mine, transport infrastructure, a manufacturing facility, a built-up area, or a campus. Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) considers effects on individuals' privacy interests -- although often only the privacy interests involved in personal data (Clarke 2009, Wright & de Hert 2012). Social impact assessment (Becker & Vanclay 2003) has a broad remit, child rights impact assessment (UoO 2013) a highly specific focus, and surveillance impact assessment (Wright & Raab 2012, Wright et al. 2015) combines technological with psychological and social impact assessment.

It is feasible to apply some such form of impact assessment approach in order to address the concerns of stakeholders generally. However, the approach is seldom consistent with any particular organisation's perceived needs, and is in direct conflict with the conventionally-assumed legal responsibility of Board directors to serve the interests of shareholders. Moreover, impact assessment of all kinds demand considerable depth and breadth of analysis, and hence considerable resources with specialist expertise.

The purpose of this article is to seek a practicable mechanism whereby the interests of relevant players can be reflected in the assessment of interventions. None of the mainstream evaluation techniques outlined in the previous section fulfils that need, because each is committed to evaluation from the viewpoint of a single stakeholder. However, one technique that is in common use for evaluating proposals from the perspective of an individual organisation may be capable of adaptation to achieve the purpose.

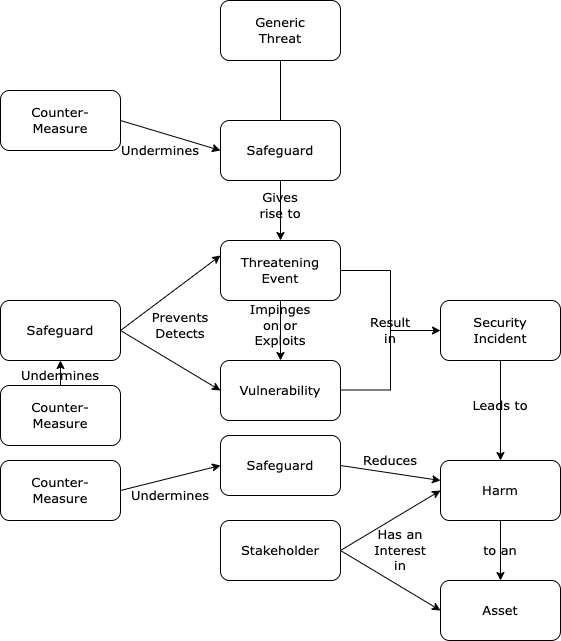

Risk Assessment has been in use for a sufficiently long period that it has become the subject of industry standardisation (ISO 27005:2011, NIST 2012, EC 2016, IEC 13010:2019). The term 'risk' refers to the perceived likelihood of harm arising to an asset as a result of a threatening event impinging on a vulnerability. The term 'security' refers to the desirable condition in which harm is prevented or mitigated because threats and vulnerabilities are subject to effective safeguards. The assessment of risk therefore needs to be based on a model of security, and meaningful conversations depend on an established terminology and sufficiently clear definitions.

In the fields of data and IT security, a substantial literature exists, and this provides a useful framework that can be drawn on in other contexts. A depiction of the security model conventional in the data and IT security fields is in Figure 1. Definitions of the terms are provided in Appendix 1. Interpretation of the terms, most crucially 'harm' and 'asset', is heavily dependent on the perspective that is adopted during the analysis. The conventional approach to risk assessment naturally adopts the perspective of the system sponsor or, more generally, the sponsoring organisation.

Extract from Clarke (2015, p.547-549)

The Risk Assessment process uses a short sequence of steps to apply the concepts in Figure 1 in order to identify and understand residual, inadequately-addressed risks, and hence lay the foundation for Risk Management (RM) activities to address them. These are embodied within an extended process model presented in the following section.

The RA technique was conceived to serve the interests of the organisation that conducts the evaluation, or that commissions the work to be performed to implement the intended intervention. Standards documents and guidelines for performing the technique reflect those origins. On the other hand, the authors have argued, in the specific context of Artificial Intelligence (AI) (Clarke (2019, p.413, Michael, Abbas et al. 2021), that:

In the present paper, the authors argue that those assertions apply not only to applications of AI, but to interventions generally, and particularly those that have substantial IT-based components. Such interventions are intrinsically socio-technical (Emery 1959, Cherns 1976, Appelbaum 1997, Mumford 2006, Abbas, Pitt & Michael 2022). They involve not just technology but also elements such as amendments to statutes, codes or contracts, adjustments to business processes that cross organisational boundaries, and the application of change management techniques to cause users who are affected by it to adjust their behaviours.

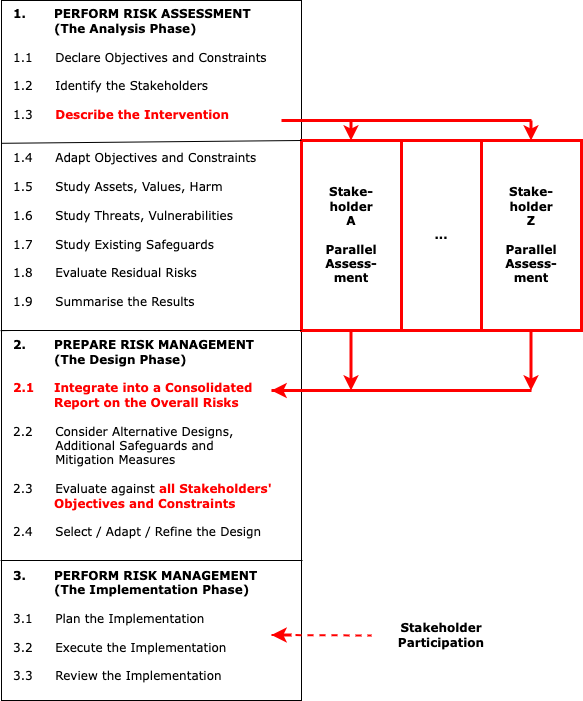

Further, the authors contend that RA is capable of adaptation to accommodate stakeholders additional to the system sponsor, in a way depicted in Figure 2, and referred to here as Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA):

Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment (MSRA) extends the conventional, organisation-internal RA process to encompass multiple, parallel assessments, all of which draw on a common base of information, but each of which is undertaken from the perspective of a particular stakeholder. The results of the various assessments are then integrated into a consolidated multi-perspective form. That integrated body of understanding is then applied during the Risk Management phases of the process.

This a further development from Clarke (2019a, p.414)

The intention is that MSRA be minimally disruptive to whatever flavour of RA each organisation currently utilises internally. An outline of the conventional RA process is provided by the sequence of steps down the left-hand side of Figure 2. This depicts RA as a series of nine steps making up the first phase of a larger process. This 'analysis' phase is followed by a 'design' phase that prepares a Risk Management (RM) plan in sufficient detail to be executable, and an 'implementation' phase that brings the plan to fruition.

The primary extension involved in transitioning from RA to MSRA is the conduct of additional instances of steps 1.4 to 1.9. This may be done:

The advantage of advocacy organisations over consultants and role-playing staff lies in their experiential base and the authenticity of their input, as evidenced by the richness of anecdotes, examples and exceptions. Advocacy organisations are in many cases poorly resourced, and in some cases entirely dependent on volunteer resources, and hence the sponsoring organisation or system sponsor may need to provide support, such as funding for travel to enable participation in key events.

To facilitate the performance of multiple, parallel risk assessments undertaken from different perspectives, it is necessary to make a small adaptation to step 1.3. A document needs to be produced and distributed that describes the intervention at a sufficient level of detail to enable each stakeholder group to undertake its own assessment. It needs to be introduced to participants through a briefing, and articulated by discussion.

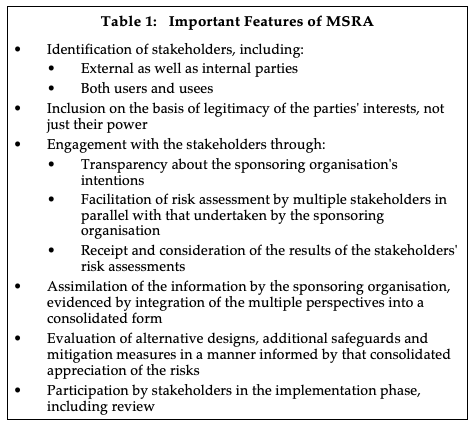

To provide effective feedforward to the RM phase, the results of the various risk assessments need to be integrated into a consolidated report (step 2.1). This needs to be introduced by a briefing and articulated by discussion, this time for the internal project team. The adequacy of the resulting Risk Management plan needs to be evaluated against this consolidation of the MSRA (step 2.3). To ensure that the stakeholders gain the intended benefits, and that the sponsoring organisation enjoys public support from the stakeholders, the loop is best closed by means of some form of stakeholder participation in the Risk Management implementation phase. The key characteristics of MSRA are listed in Table 1.

The term 'Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment' (MSRA) was adopted in Clarke (2019). Although it is a straightforward descriptor, searches of previous usage in the refereed literature have found only a few uses of the expression, of which Molarius et al. (2016) appears to be the most relevant, and Mollaeefar et al. (2020) and Karobaga (2022) the most recent. The term 'Multi-Stakeholder Risk Management' (MSRM), applicable to the subsequent phases in which the consolidated risk assessment report is applied, has also put in a small number of appearances in the literature, notably in Young & Jordan (2002) and Shackelford & Russell (2016).

In principle, an MSRA could be performed as a single, integrated, collaborative process, with all parties at the table. This approach appears appropriate where the system sponsor recognises the advantage of direct engagement with the relevant parties. The sponsoring organisation can thereby gain deep understanding, enabling the reflection of stakeholders' interests in the project design criteria and features.

In practice, however, the considerable asymmetry of information, resources and power among stakeholders is challenging to overcome. Moreover, substantial disparity exists among stakeholders' perspectives, values and dialects. Few organisations' executives, analysts and designers are likely to be able to meet the challenges involved. Conventional project development techniques certainly are not. For this reason, the technique proposed here features parallel, largely-independent RAs, each conducted by a particular stakeholder, or by a collaboration, collective, advocacy organisation or proxy representing the interests of that stakeholder. Each of the parallel activities requires information, and adequate human resources with the relevant expertise. The outcomes of the parallel studies then need to be interwoven.

The argument presented above has been almost entirely theoretical, with little evidence of practical application provided, and limited attention to the necessary economic and social drivers to motivate adoption. Three ways are suggested in which the impetus for adoption may arise. The first circumstance is where the sponsoring organisation perceives advantages in gaining an understanding of the various perspectives, accommodating the interests of other parties without bearing disproportionate cost, and keeping harm to its own interests within manageable bounds.

The second circumstance is where the system sponsor recognises obligations on the grounds of 'public policy', 'business ethics', 'corporate social responsibility' (CSR) (Hedman & Henningsson 2016), or 'environmental, social, and corporate governance' (ESG), such as that codified in the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI 2006). This appears most likely to arise in circumstances where the institutional context reinforces collaborative and human-wellbeing values. This may apply to a public agency whose mission is to deliver economic and/or social value to particular population segments, or to a corporation working under a grant or contract, or in a joint venture with other organisations that recognise a social-responsibility imperative.

The third circumstance is where a system sponsor is subject to a requirement to reflect the interests of multiple stakeholders, with a sufficiently credible threat of enforcement action to motivate compliance. This might derive from formal statutory authority, licensing conditions, 'moral suasion' by a powerful regulatory agency, or aspects of the institutional environment, such as widely-adopted industry standards, or cultural conventions within the industry sector or country.

The remainder of this section tests whether the proposition has potential by seeking out circumstances in which at least some of the key characteristics of MSRA listed in Table 1 are apparent.

The first question addressed is whether MSRA can assist with the efficient detection of issues. Instances of MSRA-like activities can be seen in environmental contexts. Environmental Impact Assessment procedures are formal and cumbersome. Where an intervention is less dramatic, but still potentially impactful, an MSRA can assist in identifying and understanding the concerns of interest groups. Fire stations, which store dangerous chemicals and train firemen in using them, are inevitably close to watercourses that harbour frogs and whose surroundings are used for children's leisure activities. When mining companies intend to extract ore from an area that is subject to a degree of environmental or indigenous protection, MSRA can assist the company to appreciate the possibly complex, contested, vague and/or conflicting concerns of such groups. In addition to fulfilling informational needs, conduct of an MSRA evidences to stakeholders, the public, the media and regulators that the organisation has taken due care, and sought to act responsibly.

A second area of contribution relates to achieving efficiency in engagement. When a government agency is preparing to close an operational facility that is a major employer in a regional city or town, it may be politically necessary, reputationally advisable and/or morally responsible, to openly discuss the impact of the closure, taking into account the circumstances of many segments of society, and both economic and social effects. Similar challenges arise with the closure of large-scale corporate ventures in such industries as resource-extraction, steel-making and car-assembly. At least modest contributions to mitigation measures may be needed. MSRA is a fit to the need because it is a variant of the company's existing risk assessment processes.

Another area is efficient investigation and controlled experimentation in relation to inherently dangerous products. Medical implant designers undertake carefully-designed pilot studies, with active participation by multiple health care professionals, patients, and patient advocacy organisations. Regulatory schemes play a key role in encouraging developers' awareness of stakeholders' needs, and of the scope for collateral damage (ISO 14971:2019).

Highly-networked industry sectors such as health and international trade, and major infrastructure installations such as sea-ports and airports, are not organised as linear supply-chains, nor in a hub-and-spoke or star configuration. They feature many specialised enterprises, and many inter-linkages and flows among those enterprises, overlaid by considerable regulatory interference to satisfy such public-interest needs as public safety, hygiene, service quality and tax-collection. Changes to architecture, infrastructure, data flows and business processes depend on effective negotiation among many players. MSRA has attributes that satisfy many of those needs (Clarke 1994, Cameron 2009).

A further cluster of examples exists in the area of efficient electronic markets. A government seeking to break open a monopoly marketspace and overcome entrenched, excessive profit-making and stultification of innovation, could use an MSRA to expose the impacts of the current arrangements, gain public support for the initiative, and shame the beneficiaries of the monopoly into accepting the need for change (Neo 1992). A similar initiative was driven by one side of a marketspace. It featured livestock producers, distant from major population-centres, and facing high costs to get their stock to saleyards and low prices offered for their product by well-informed agents for supermarket chains in so-called 'farm-gate private treaties'. The producers' association applied elements of the MSRA notion to develop an online auction scheme. The result was reduced information asymmetry in the marketspace, and a better balance among the market-participants' interests (Clarke & Jenkins 1993).

A more recent form of sectoral transformation is commonly referred to as the 'technology platform' model. Disruptors from eBay (since 1995) to Uber (2009), and many other aspirants, have taken advantage of new technology and the start-up's lack of legacy technology and a well-paid labour force, by deploying new services at a speed large, established corporations simply cannot replicate. Case studies have highlighted failures by regulatory agencies to enforce existing laws, to the deep disadvantage of heavily-regulated incumbents (Wyman 2017, Clarke 2022, Michael 2022). The dislocation and financial losses suffered by investors and employees, and loss of amenity by communities, would have been mitigated had regulators applied MSRA, because it would have supported the development of a transition strategy that enabled progress without such dramatic negative consequences.

Many of the elements of MSRA are evident in these vignettes. Usees appear as the children in the nearby playground, the dependents of the employees displaced when 'big steel' closes, the families of people with leaky silicone implants, and the retirees with their retirement funds invested in taxi-plates. Stakeholder power appears to matter most, but legitimacy puts in an appearance in environmental and indigenous matters, in large-scale government agency closures, in medical implant issues, and in the contexts of livestock buyers and sellers, and income-earners forced to accept casualised employment and piece-work.

The preceding section identified potential drivers for adoption of MSRA, and multiple circumstances in which some of the key aspects of MSRA are evident. This section adopts a complementary approach, by seeking the greater depth afforded by a case study. No case is available that expressly applies the newly-defined technique. We selected a transformative IT project that was run during the period 2015-22 by a large Australian government agency. We judged it to be suitable because it was an unsuccessful intervention that included a significant IT component, it had substantial impacts on both users and usees, and it was sufficiently well-documented to support the analysis.

Australia is a nation of 25 million people, with a substantial 'safety-net' and well-developed welfare-benefits administration mechanisms. The portfolio agency responsible for operations is the Department of Human Services (DHS), whose Centrelink Division runs a vast database, performs fortnightly payment processes that transfer over AUD150 billion p.a. to millions of clients, and operates client-interaction facilities in the forms of web-sites, interactive voice response (IVR), call-centres and over 300 physical service centres.

The agency's operations have a strong focus on management of the enormous scope for fraud, error and waste. An aspect of particular significance is the checking of the fortnightly statements of income by clients of some of the programs, which affect the amount of the next fortnight's payments. The processes to detect and recover overpayments have included data matching programs for over four decades, with the earliest documented instance dating to 1978 (Clarke 1994b).

In 2015, DHS was lured by the hype about 'transformative IT' into proposing a further level of automation of overpayment detection, debt recognition, and debt recovery, with the expectation of reaping billions of dollars in reduced overpayments and labour costs. The project was officially referred to as the Online Compliance Intervention (OCI), but was soon dubbed by the media 'Robodebt'. It has been the subject of a number of official reviews, and published case studies are now appearing in the refereed literature (Rinta-Kahila 2022). This section is underpinned by Clarke, Michael & Abbas (2022), which cites many official and refereed sources, complemented by some media sources.

DHS initiated the project in 2015, with initial roll-out in July 2016, and full-scale roll-out from September 2016. The key features of the design are listed in Table 2. Briefly, suspects were generated by matching data acquired from two different agencies, necessarily making some assumptions about the apportionment of each welfare client's taxable earnings to particular time-periods. Apparent anomalies resulted in automatic despatch of letters to suspect clients, requiring each client to provide documentation relating to their earnings in particular fortnights between 2 and 7 years earlier. If a client failed to respond or to satisfy the demand for evidence, a debt was automatically declared to exist, and collection processes were instigated. In the case of ongoing clients, the alleged overpayments were clawed back through deductions from later welfare payments; whereas, if the person was no longer a client, DHS passed the ex-client's details to a debt collector.

| DHS Action | Observations | |

| 1 | Data matching of client income data as declared to the taxation authority (mostly annually after year's end) with client income data declared directly to DHS (on a fortnightly basis shortly after each fortnight's end) | A new data matching scheme was created, avoiding the use of the purpose-designed 'Tax File Number' identifier, and thereby circumventing an established regulatory regime |

| 2 | Inference of apparent overpayment if a material difference was found between the apportioned income from the taxation authority and the declared fortnightly income in DHS's own files | This was acknowledged by DHS to be an inherently risk-prone inference, which had previously only been used internally, and subject to human review |

| 3 | Automated letters of demand to clients about whom inferences had been drawn regarding apparently inconsistent income declarations, requiring the production of specified evidence | Collection of evidence from employers had previously been undertaken by DHS, under authority of law. Outsourcing this work to clients inverted the onus of proof, and imposed it on people who lack the power to issue their employers with demands for copies of documents |

| 4 | Clients were subjected to an inflexible, inadequate and unfriendly website-driven process | Many clients were unable to understand the instructions and interface, let alone perform the required tasks |

| 5 | In the absence of a response, or if documentation received was deemed inadequate, DHS raised a debt, and auto-deducted from future payments, or used debt-collection agents | Most clients had insufficient information available to even understand let alone challenge the debt |

Within weeks of the launch, the number of debt notices skyrocketed from 20,000 per annum to 20,000 per week. All client channels to DHS were hopelessly overloaded. By December 2016, media coverage was documenting the harrowing experiences of clients subjected to the scheme. Multiple logical and process flaws were apparent, many of them associated with the automated nature of 'Robodebt'.

DHS and the responsible Minister stonewalled. Whistleblowers emerged from among the very large base of employees and contractors. The Ombudsman commenced an investigation of a few, narrow aspects of the process. A Senate Committee launched a longer, slower, but broader Inquiry.

In April 2017, a Report by the Ombudsman identified some significant problems, and wrung minor concessions out of DHS. In May 2017, the Senate Committee's first report identified far more inadequacies, and documented considerable harm to individuals, arising from material inferencing errors, in many instances so seriously wrong that no debt existed at all.

Despite ample evidence in early 2017 that the basis on which the scheme was built was fundamentally flawed, the Government and DHS refused to do anything constructive to address the problems the scheme was giving rise to, and continued with the discredited scheme over an operational life of 40 months, 2016-19. In excess of 1 million letters were sent to clients. 433,000 people had debts imposed on them, totalling AUD1.7 billion. 381,000 individuals were pursued, in many cases by private debt collection agencies, and repaid over AUD750m.

It took until November 2019 for the government to accept defeat, and cease raising debts on the basis of averaged taxation data. This appears to have been forced by an imminent case that DHS had inadvertently let slip through to the courtroom. It took a further 6 months, until May 2020, for the Attorney-General to concede that all Centrelink debts raised using the income averaging method were unlawful.

In defending a class action, DHS breached its legal obligations under a Legal Services Direction, by acting as anything but a 'model litigant', and fighting the case all the way to the court door. The Senate Committee's final report, and the judge's comments when approving the agreement to settle the class action, were scathing of the agency's behaviour.

Many of the individuals materially affected by the scheme were vulnerable, variously financially, educationally, or in terms of physical disability and/or mental health. Most clients were users -- although some were not, due to a lack of computing or communications facilities or of an accessible service-centre, or of physical or mental capacity. Further, multiple categories of 'usees' were apparent including carers, dependents of social welfare clients, householders of social welfare clients, mothers (of clients at risk of self-harm, including multiple documented suicides), financial counsellors, psychological counsellors, lawyers and the services employing them.

The financial dimension of the fiasco totalled over AUD2 billion. In The Netherlands, a much smaller scandal in 2020 resulted in an entire government resigning (Erdbrink 2021). In Australia, however, the principle of Ministerial responsibility no longer exists, and none of the six Ministers involved suffered any consequences. Nor did any of the senior executives of DHS.

IT systems in the public sector are confronted by a substantial set of challenges, including scale, complexity, a multiplicity of stakeholders, diversity and conflict among the interests of the stakeholders, legal constraints, and rapidly-changing political priorities. As a result, many IT-based interventions in the public sector perform poorly, are dysfunctional, or are outright failures. A rational strategy for risk-averse executives is to look for approaches that can ensure success, or, if complete success is not achievable, can support a claim of some degree of success, or, at worst, enable the avoidance of having to acknowledge failure.

This section illustrates application of the MSRA technique, as described in section 4.2 above, to the case of Robodebt. Four approaches to applying MSRA are considered. The first is proactive, and is the technique's primary intended mode of use. Two negative approaches to its use are considered, one with a focus on contingency planning, the other entirely reactive. The fourth is bolder, adopting a strategic attitude. Each approach is illustrated using elements of the Robodebt case study, and the case then used as a basis for imaginary vignettes that identify ways in which the elements of MSRA could have been constructively applied in that real-world context.

The design purpose of MSRA is that it be used in a proactive manner, in advance of implementation, even in advance of design, and even in parallel with, or integrated with, the preliminary requirements analysis phase. In the Robodebt case, however, it is challenging to identify any indication of any aspect of MSRA having been even considered, let alone applied.

During preliminary steps 1.1 to 1.3, an overview of the requirements and conceptual design could have been provided to a few key stakeholders. If the Minister or senior executives were nervous about excessive information exposure, advocacy organisations could have been invited that were less powerful, less activist, or even captive. Some of the insights arising would have been likely to influence all but the most committed authoritarians and technocrats in the agency and the Minister's office. The process would also have empowered staff who were aware of the real-world risks, enabling them to table their concerns in the form of clarifications of statements made by outsiders. Because no such process took place, a key opportunity was missed for early detection that the propositions were misconceived.

If, after these preliminary skirmishes, the agency had persisted with the project, the main body of the risk assessment activity (steps 1.4 to 1.9) would have followed. Evidence exists that no advantage was taken even of the experience of the agency's own specialist compliance and IT systems staff. Those employees and contractors were forced to administer a scheme that they recognised from the beginning as being deeply flawed. At the very least, the enlistment of internal expertise as a weak proxy source of stakeholders' concerns would have represented a valuable element of risk assessment and management.

A second, rather negative approach might be attractive to organisations that operate in a secretive manner. It would be natural for them to regard stakeholders as at least competitors, even adversaries, and the provision of information to stakeholders as 'inviting the barbarian inside the gates'. Even in circumstances in which such hostility exists, MSRA may be capable of delivering value to the sponsoring organisation, and conceivably even to stakeholders. It can do that by providing information that enables the sponsoring organisation to anticipate possible actions by stakeholders, and make preparations to deal with them.

Rather than engaging with advocates for stakeholders, an organisation can hire a proxy to provide insights into the views of stakeholders. In particular, a consultancy with expertise in the area can be commissioned to perform parallel studies from the viewpoints of particular stakeholder groups (applying steps 1.4-1.9, and 2.1-2.3), or even just to identify issues and risks. That can provide insights into stakeholder concerns, and advocacy organisation agitation that may need to be pre-countered. Scenarios can be developed, and a bank of public relations plans, media briefings, and media releases drafted, ready for deployment in the event that particular contingencies arise. Stakeholders might still benefit, if the contingency plans include adaptation of key features, or the implementation or even preparatory design of mitigation measures.

In the Robodebt case, some evidence exists of public relations plans. Ministerial statements were promptly issued, conveying that the government was tackling welfare cheating. Successive statements 'stayed on message' (suggesting that 'a message' had been previously agreed). On the other hand, no evidence was found suggesting that the public relations plans were informed about the nature and intensity of stakeholders' concerns.

That second approach reflects an entirely negative standpoint on the part of the sponsoring organisation. This third, reactive, approach is relevant where the organisation has instead been passive, has failed to perform any preparatory work, and is forced to respond quickly to, for example, serious pushback from users, significantly negative media coverage, or regulatory intervention.

A cynical form of co-option of MSRA can be of benefit to the sponsoring organisation. For example, elements of it could be moulded into a 'charm offensive'. This would have its focus on steps 2.2 (alternative designs, additional safeguards and mitigation measures) and 2.4 (refinement of the design). The new work can be projected as being pre-planned 'continual improvement' (ISO 9001:2015). Key advocacy organisations and/or media players could be invited into the Ministerial office, for a 'heart-to-heart' discussion. This could be accompanied by public assurances that the messages have been heard and are being acted upon. A trickle of announcements of minor adjustments could be provided, aimed at being attractive to the more powerful or noisier stakeholder groups, and dressed up for the media, for example by showcasing individuals who have benefited from the project.

Even at this late stage, a less cynical, but nonetheless reactive approach could deliver benefits to stakeholders as well as the sponsoring organisation. Risk management steps 2.2 and 2.4 can be used to devise adaptations to the system that have significant impacts on its problematic features, including additional safeguards and additional mitigation measures. A rapid but ab initio risk assessment could be conducted, incorporating the now-apparent perspectives of the more powerful among the affected users and usees, and perhaps actively involving advocacy organisations or at least proxies for them. This in effect compresses the parallel phases 1.4 to 1.9 into a single, joint activity and articulates it directly into 2.1 (integration into a risk assessment report that reflects multiple viewpoints).

In the Robodebt case, the main evidence of adjustments by the agency was minor changes made around the time of the Ombudsman's investigation about 3-6 months after commencement in 2016. They appear to have been designed primarily to gain supportive comments from the oversight agency that could be used as a defence against subsequent rounds of criticism. Once again, MSRA offers opportunities that could have assisted the sponsoring organisation in what had quickly become a disaster management process.

A further insight that reactive use of MSRA may lead an agency towards is the benefit of having early warning systems in place, and of institutionalising ways to communicate to executives the messages coming through those channels. In the Robodebt case, vastly increased volumes of particular transaction-types were evident. Complaints systems, and shortly after that formal disputes, were rapidly increasing. Public opprobium was quickly emerging in the media, of evidentiary quality far better than vague anecdotes. By ensuring that negative feedback could trigger recognition of the need for responses and adaptations, the agency could have reduced the damage to itself, and to other stakeholders.

The fourth approach is appropriate for sponsoring organisations that are mature enough to adopt a positive, strategic stance at corporate rather than merely project level. Executives may appreciate that the expression of policies, and the design of business processes and supporting systems, will always be perceived quite differently by diverse stakeholder groups. They may therefore recognise the benefits of internalising familiarity with those groups and their perspectives, and institutionalising channels of communication between them and the agency. A means for doing this is a 'reference group', comprising enough advocacy organisations to adequately encompass key interests, but small enough that coherent discussions can occur.

Periodic meetings of the reference group can be held in which agency staff and members of the reference group interact. Some events can address matters that relate to organisation-wide functions (such as reflection of ethnic and lingual diversity, and appeals and redress processes). Other events can relate to particular interventions that are being considered, designed, or adapted. To convey to contributors that the organisation has a commitment to listening, and to reflecting the messages provided to them, meaningful reports need to be provided back to reference group members shortly after each event, and a list of 'open issues' and their resolution needs to be created and maintained.

In the Robodebt context, the agency has comprehensive responsibilities in relation to the operational aspects of all national welfare benefits schemes. The primary user and usee segments, and the primary advocacy organisations active in each segment, should be very familiar to relevant senior staff within the agency. Active players on behalf of welfare recipients are easily identified. The Senate Committee Inquiry into Robodebt received submissions from 62 such organisations, which can be readily categorised as shown in Table 3.

No evidence has been found of the agency responsible for the Robodebt project operating a reference group of welfare advocacy organisations. Use of MSRA by the agency within a strategic approach would have offered the agency's executives and project staff ample opportunity to understand both other perspectives and the intensity of feeling of users and usees. Interactions would have drawn attention to specific features of the intended scheme that appeared especially problematical, and identified client-segments likely to be particularly badly affected, and contingencies that had not been considered. Armed with that information, the agency would at least have been able to implement mitigation measures, reduce the degree of indignation among advocacy organisations and hence their level of activism on the matter, and avoid some of the most damaging aspects of subsequent media exposure.

The rationale underlying MSRA is that its core is well-known to organisations and the consultancies that support them, and is already used by them, in many cases perhaps perfunctorily, but in some cases to good effect. Conventional risk assessment is conducted from the perspective of the sponsoring organisation. The MSRA process grafts additional, parallel analyses onto the main stream of assessment, then draws the findings of each of the stakeholder analyses back into the main stream, integrating them into a consolidated view. The result is a risk management plan founded on insights from multiple perspectives. The sponsor gains because its projects are far less likely to encounter serious turbulence, and far less likely to fail. Users and usees gain because collateral damage is greatly reduced, and mitigation measures are included in the scheme to deal with the instances that do arise.

In the Robodebt case, the agency appears not to have a strategic view of stakeholder interactions, despite its central role in the distribution and management of welfare payments. It also failed to adopt a proactive approach to a specific intervention, despite its transformative nature. It therefore appears to be too immature to recognise the value of the first, proactive approach to applying MSRA and the fourth, strategic approach.

Evidence exists that the agency has some capacity to plan for contingencies. Had its staff been familiar with MSRA, it may have been able to apply the second approach (contingency-planning), in which case it may have gained sufficient insight to at least cushion the negative impacts on users, usees, the agency's reputation, and the public purse.

The agency demonstrated very little capacity to assimilate new information, learn from it, and adapt its design. Even so, had MSRA been applied using the third and least-useful approach (reactive), particularly if it had been adopted once the media barrage had reached a crescendo 3-4 months after launch, in early 2017, enough insight might have been accumulated in a short time to enable mitigation of the harm to all parties. Even in compromised form, MSRA appears capable of assisting sponsoring organisations to avoid disasters.

Interventions into socio-economic systems involve many elements, including the application of powerful IT, which is increasingly being extended to automated inferencing, decision-making and action. Large-scale, impactful interventions need to be evaluated, not just implemented. Many assessment techniques have a tight focus on the interests of the system sponsor. There are few drivers for the inclusion of other stakeholders in assessment processes. To the extent that other stakeholders' interests are reflected, it is because those parties have sufficient power.

The scope of IT-based systems has expanded from single functions within an organisation, to multiple functions across organisational boundaries and beyond those boundaries, out to individuals. Such systems are inherently socio-technical and cannot be meaningfully considered as mere technological artefacts. Meanwhile, stakeholders that merely have legitimacy and/or urgency have suffered depredations from interventions, because system sponsors have not been attuned to their interests. In many cases, harm to their interests can be avoided, or at least mitigated, and even some benefits delivered to them, with only limited compromise to the sponsor's objectives, if legitimate stakeholders' needs are factored into the design. Further, if those stakeholders' needs are understood at an early stage, the costs of addressing them may not be great.

Even if the will exists to reflect stakeholders' legitimacy as well as their power, there are challenges in finding suitable evaluation techniques to apply. Business Case Development is primarily driven by the prospects of profit or cost-savings, or the need to demonstrate compliance with regulatory requirements. Most of the variants of Impact Assessment concern themselves with particular categories of effect that interventions may have. Technology Assessment is concerned with a broad technology with many capabilities, which may give rise to a variety of interventions into economic and social systems, so, despite it being highly informative, its influence is dissipated across many contexts.

The well-developed technique of Risk Assessment, despite being a creature of rational enterprise management, may harbour the best prospects for reflecting the interests of multiple stakeholders. Scans for potential drivers for the adoption of the MSRA technique identified a variety of contexts in which some of its hallmarks are evident. The application of MSRA was illustrated by considering a large-scale government initiative whose misconceptions gave rise to considerable cost to the public purse, and seriously harmed many users, and many usees. The case study material enabled the identification of four alternative approaches to the application of MSRA, respectively proactive, contingency-planning, reactive and strategic in nature. Implementation of MSRA incurs cost; but changes during the analysis and conceptual design phases are vastly less expensive than belated efforts to rebuild an already-operational system.

On the basis of these preliminary evaluations, exposure of the proposal is appropriate, followed by experimentation and trialling, in order to establish whether MSRA can be a practicable mechanism to achieve the reflection of interests of the relevant players in the assessment of interventions. Further work is required to investigate the scope for integration of MSRA with systems analysis, design, implementation and continual improvement processes. Consideration also needs to be given to the application of MSRA in contexts in which the notion of a singular sponsoring organisation or system sponsor is inadequate, because the sponsor is a joint venture, an industry-wide scheme, or a public-private partnership, or is a broad multi-organisational network or ecosystem.

Abbas R., Pitt J., & Michael K. (2021) 'Socio-technical design for public interest technology' IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 2,2 (2021) 55-61

Achterkamp M.C. & Vos J.F.J. (2008) 'Investigating the use of the stakeholder notion in project management literature, a meta-analysis' Int'l J. Project Management 26, 7 (October 2008) 749-757

Ackermann F. & Eden C. (2011) 'Strategic management of stakeholders: Theory and practice' Long range planning 44,3 (2011) pp.179-196, at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Colin-Eden/publication/222804628_Strategic_Management_of_Stakeholders_Theory_and_Practice/links/56fe476908ae1408e15cfc05/Strategic-Management-of-Stakeholders-Theory-and-Practice.pdf

Appelbaum S.H. (1997) 'Socio-technical systems theory: an intervention strategy for organizational development' Management Decision 35,6 (1997) 452--463, at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Steven-Appelbaum/publication/235266179_Socio-technical_systems_theory_An_intervention_strategy_for_organizational_development/links/0a85e52f1456d0bcff000000/Socio-technical-systems-theory-An-intervention-strategy-for-organizational-development.pdf

Barrett S. & Konsynski B. (1982) 'Inter-Organization Information Sharing Systems' MIS Quarterly 6, 4 (December 1982) 93-105

Baumer E.P.S. (2015) 'Usees' Proc. 33rd Annual ACM Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI'15), April 2015, at https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/2702123.2702147

Becker H. & Vanclay F. (2003) 'The International Handbook of Social Impact Assessment' Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2003

Berleur J. & Drumm J. (Eds.) (1991) 'Information Technology Assessment' Proc. 4th IFIP-TC9 International Conference on Human Choice and Computers, Dublin, July 8-12, 1990, Elsevier Science Publishers (North-Holland), 1991

Bryson J.M. (2004) 'What to do when stakeholders matter: stakeholder identification and analysis techniques' Public Management Review 6,1 (2004) 21-53, at https://ftms.edu.my/images/Document/MOD001074%20-%20Strategic%20Management%20Analysis/WK3_SR_MOD001074_Bryson_2004.pdf

Cameron J. (2009) 'An integrated framework for managing eBusiness collaborative projects' PhD Thesis, UNSW, September 2009, at https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/13ce09cb-ee14-456c-87a3-5e7547a4a2e4/full

Cherns A. (1976) 'The principles of sociotechnical design' Human Relations 29,8 (1976) 783-792

Clarke R. (1992) 'Extra-Organisational Systems: A Challenge to the Software Engineering Paradigm' Proc. IFIP World Congress, Madrid, September 1992, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/SOS/PaperExtraOrgSys.html

Clarke R. (1994a) 'EDI in Australian International Trade and Transportation' Proc. 7th EDI-IOS Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 6-8 June 1994, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/Bled94.html

Clarke R. (1994b) 'Dataveillance by Governments: The Technique of Computer Matching' Information Technology & People 7,2 (December 1994) 46-85, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/MatchIntro.html

Clarke R. (2009) 'Privacy Impact Assessment: Its Origins and Development' Computer Law & Security Review 25, 2 (April 2009) 123-135, at http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/PIAHist-08.html

Clarke R. (2015a) 'The Prospects of Easier Security for SMEs and Consumers' Computer Law & Security Review 31, 4 (August 2015) 538-552, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/SSACS.html#App1

Clarke R. (2015b) 'Not Only Horses Wear Blinkers: The Missing Perspectives in IS Research' Keynote Presentation, Proc. ACIS'15, at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1611.04059

Clarke R. (2019a) 'Principles and Business Processes for Responsible AI' Computer Law & Security Review 35, 4 (2019) 410-422, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/AIP.html#MRM

Clarke R. (2019b) 'Risks Inherent in the Digital Surveillance Economy: A Research Agenda' Journal of Information Technology 34,1 (Mar 2019) 59-80, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/DSE.html

Clarke R. (2022a) 'Research Opportunities in the Regulatory Aspects of Electronic Markets' Electronic Markets 32, 1 (Jan-Mar 2022) 179-200, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/RAEM.html

Clarke R. (2022b) 'Evaluating the Impact of Digital Interventions into Social Systems: How to Balance Stakeholder Interests' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, May 2022, at http://rogerclarke.com/DV/MSRA-VIE.html

Clarke R. & Davison R.M. (2020) 'Through Whose Eyes? The Critical Concept of Researcher Perspective' J. Assoc. Infor. Syst. 21, 2 (March-April 2020) 483-501, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/RP.html

Clarke R., Davison R.M. & Jia W. (2020) 'Researcher Perspective in the IS Discipline: An Empirical Study of Articles in the Basket of 8 Journals' Information Technology & People 33, 6 (October 2020) 1515-1541, PrePrint at http://rogerclarke.com/SOS/RPBo8.html

Clarke R. & Jenkins M. (1993) 'The strategic intent of on-line trading systems: a case study in national livestock marketing' Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2, 1 (March 1993) 57-76, PrePrint at http://www.rogerclarke.com/EC/CALM.html

Clarke R., Michael K. & Abbas R. (2022) 'RoboDebt: An Exemplary Case Study of Public Sector Irresponsibility' Working Paper, Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, September 2022, at http://rogerclarke.com/EC/RDCS.html

Dikov D. (2020) 'Using the Net Present Value (NPV) in Financial Analysis' Magnimetrics, 2020, at https://magnimetrics.com/net-present-value-npv-in-financial-analysis/

Dwivedi Y.K., Wastell D., Laumer S., Henriksen H.Z., Myers M.D., Bunker D., Elbanna A., Ravishankar M.N. & Srivastava S.C. (2015) 'Research on information systems failures and successes: Status update and future directions' Information Systems Frontiers, 17(1), 143--157, at https://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa21511/Download/0021511-16122015173731.pdf

EC (2016) 'EU general risk assessment methodology' European Commission, 2656912, June 2016, at https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/17107/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

Emery F. (1959) 'Characteristics of socio-technical systems' In 'The Social Engagement of Social Science: A Tavistock Anthology' Volume 2. pp. 157-186), University of Pennsylvania Press

Erdbrink T. (2021) 'Government in Netherlands Resigns After Benefit Scandal', The New York Times, 15 Jan 2021, at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/15/world/europe/dutch-government-resignation-rutte-netherlands.html

Fischer-Huebner S. & Lindskog H. (2001) 'Teaching Privacy-Enhancing Technologies' Proc. IFIP WG 11.8 2nd World Conference on Information Security Education, Perth, Australia, 2001

Freeman R.E. & Reed D.L. (1983) 'Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance' California Management Review 25, 3 (1983) 88-106

Garcia L. (1991) 'The U.S. Office of Technology Assessment' Chapter in Berleur J. & Drumm J. (eds.) 'Information Technology Assessment' North-Holland, 1991, at pp.177-180

Hedman J. & Henningsson S. (2016) 'Developing Ecological Sustainability: A Green IS Response Model' Information Systems Journal 26, 3 (2016) 259-287

IEC 31010:2019 'Risk management -- Risk assessment techniques' International Standards Organisation, 2019

ISO 14971:2019 'Medical devices - Application of risk management to medical devices' International Standards Organisation, 2019

ISO 27005:2011 'Information technology-Security techniques-Information security risk management' International Standards Organisation, 2011, especially pp. 7-17 and 33-49

ISO 9001:2015 'Quality management systems - Requirements' International Standards Organisation, 2015

Karaboga M. (2022) 'Datenschutzrechtliche Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten jenseits der Ermächtigung des Individuums: Die Multi-Stakeholder-Datenschutz-Folgenabschätzung' In Friedewald M., Kreutzer M. & Hansen M. (eds) 'Selbstbestimmung, Privatheit und Datenschutz', DuD-Fachbeiträge, Springer Vieweg, April 2022, at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-33306-5_14

Laplume A.O., Sonpar K. & Litz R.A. (2008) 'Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us' Journal of Management 34,6 (2008) 1152-1189

Mitchell R.K., Agle B.R. & Wood D.J. (1997) 'Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts' Academy of Management Review 22, 4 (1997) 853-886

Molarius R., Raeikkoenen M., Forssen K. & Maeki K. (2016) 'Enhancing the resilience of electricity networks by multi-stakeholder risk assessment: The case study of adverse winter weather in Finland' Journal of Extreme Events 3, 4 (2016)

Mollaeefar M., Siena A. & Ranise S. (2020) 'Multi-stakeholder cybersecurity risk assessment for data protection' Proc. 17th Int'l Conf. on Security and Cryptography-SECRYPT, pp. 349-356, at https://cris.fbk.eu/bitstream/11582/322586/1/Multi-Stakeholder%20Cybersecurity%20Risk%20Assessment%20for%20Data%20Protection.pdf

Morgan R.K. (2012) 'Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art' Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 30, 1 (2012) 5-14, at https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.661557

Mumford E. (2006) 'The story of socio-technical design: reflections on its successes, failures and potential' Info Systems J 16 (2006) 317--342, at https://executiveinsight.typepad.com/files/the-story-of-socio-technical-design.pdf

Neo B.S. (1992) 'The implementation of an electronic market for pig trading in Singapore' Journal of Strategic Information Systems 1, 5 (December 1992) 278-288

NIST (2012) 'Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments' US National Institute for Standards and Technology, SP 800-30 Rev. 1 Sept. 2012, pp. 23-36, at https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-30/rev-1/final

OTA (1977) 'Technology Assessment in Business and Government' Office of Technology Assessment, NTIS order #PB-273164', January 1977, at http://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk3/1977/7711_n.html

Pouloudi A. & Whitley E.A. (1997) 'Stakeholder Identification in Inter-Organizational Systems: Gaining Insights for Drug Use Management Systems' Euro. J. of Information Systems 6, 1 (1997) 1-14

Rinta-Kahila T., Someh I., Gillespie N., Indulska M. & Gregor S. (2022) 'Algorithmic decision-making and system destructiveness: A case of automatic debt recovery' European Journal of Information Systems 31,3 (2022) 313-338, at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0960085X.2021.1960905?needAccess=true

Shackelford S.J. & Russell S. (2016) 'Operationalizing Cybersecurity Due Diligence: A Transatlantic Case Study' South Carolina Law Review 67, 3 (Spring 2016) 7, at https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4182&context=sclr

Schmidt M.J. (2005) 'Business Case Essentials: A Guide to Structure and Content' Solution Matrix , 2005, at http://www.solutionmatrix.de/downloads/Business_Case_Essentials.pdf

SoW (2013) 'Discounted Cash Flow Analysis' Street of Walls, 2013, at https://www.streetofwalls.com/finance-training-courses/investment-banking-technical-training/discounted-cash-flow-analysis/

Stobierski T. (2019) 'How To Do a Cost-Benefit Analysis & Why It's Important' Harvard Business School Online, September 2019, at https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/cost-benefit-analysis

UNPRI (2006) 'What are the Principles for Responsible Investment?' UNPRI, 2006, at https://www.unpri.org/about-us/what-are-the-principles-for-responsible-investment

UoO (2013) 'Bringing Children in from the Margins: Symposium on Child Rights Impact Assessments, Child Rights Impact Assessment: A Tool to Focus on Children' University of Ottawa, 14-15 May 2013, at http://www.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/imce_uploads/report_from_cria_symposium_may2013_canada.pdf

Wahlstrom K. & Quirchmayr G. (2008) 'A Privacy-Enhancing Architecture for Databases' Journal of Research and Practice in Information Technology 40, 3 (August 2008) 151-162, at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.454.3815&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Wright D. & De Hert P. (eds) (2012) 'Privacy Impact Assessments' Springer, 2012

Wright D., Friedewald M. & Gellert R. (2015) 'Developing and testing a surveillance impact assessment methodology' International Data Privacy Law 5, 1 (2015) 40-53, at https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/data-crone-wright-2015a.pdf

Wright D. & Raab C.D. (2012) 'Constructing a surveillance impact assessment' Computer Law & Security Review 28, 6 (December 2012) 613-626, at https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/data-crone-wright-2012a.pdf

Wyman K.M. (2017) 'Taxi Regulation in the Age of Uber' N.Y.U. J. Legislation & Public Policy 20, 1 (April 2017) 1-100, at https://www.nyujlpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Wyman-Taxi-Regulation-in-the-Age-of-Uber-20nyujlpp1.pdf

Young R.C. & Jordan E. (2002) 'IT Governance and Risk Management: an integrated multi-stakeholder framework' Asia Pacific Decision Sciences Institute, Bangkok, 2002, at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.454.3272&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Adapted version of Clarke (2015, p.547-549)

This paper draws on and extends previous work undertaken by the authors on the reflection of stakeholder interests in socio-technical systems, on stakeholder-oriented risk assessment in the context of applications of AI, and on digitalisation, including in the digital surveillance economy and digital platforms. The term Multi-Stakeholder Risk Assessment was first used in the manner relevant to this paper in a refereed article relating specifically to the responsible application of AI (Clarke 2019a). A working paper that first articulated MSRA was prepared by one of the authors, and was presented at the International Digital Security Forum (IDSF22) in Vienna on 1 June 2022 (Clarke 2022b).

Roger Clarke is Principal of Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, Canberra. He is also a Visiting Professor associated with the Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation in UNSW Law, and a Visiting Professor in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University.

Katina Michael is a Professor at Arizona State University, a Senior Global Futures Scientist in the Global Futures Laboratory and has a joint appointment in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence. She is the director of the Society Policy Engineering Collective (SPEC) and the Founding Editor-in-Chief of the IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society.

| Personalia |

Photographs Presentations Videos |

Access Statistics |

|

The content and infrastructure for these community service pages are provided by Roger Clarke through his consultancy company, Xamax. From the site's beginnings in August 1994 until February 2009, the infrastructure was provided by the Australian National University. During that time, the site accumulated close to 30 million hits. It passed 65 million in early 2021. Sponsored by the Gallery, Bunhybee Grasslands, the extended Clarke Family, Knights of the Spatchcock and their drummer |

Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd ACN: 002 360 456 78 Sidaway St, Chapman ACT 2611 AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 2 6288 6916 |

Created: 8 January 2022 - Last Amended: 20 October 2022 by Roger Clarke - Site Last Verified: 15 February 2009

This document is at www.rogerclarke.com/DV/MSRA.html

Mail to Webmaster - © Xamax Consultancy Pty Ltd, 1995-2022 - Privacy Policy